Manuel Munoz and I sit on sofas in the lounge of the Mason Pond Inn in Virginia. The rain nuzzles the windows and Manuel glances out, he seems bemused at the scenery of rain. This tawny inhabitant of the Arizona cactus country. His voice is faintly granular and soft as sand. Manuel was reared in the small town of Dinuba in California’s Central Valley. He is bold in his writing, shy in manner, a film aficionado. His body cuts a lean muscular form on the sofa. He wears dark jeans and a collared t-shirt. A chiseled jaw, thick raven black hair gelled into spikes, but his eyes are the thing. Large and tapering attractively at the corners, they lure with all the possibilities of the moment. One feels the charm in it.

Manuel Munoz and I sit on sofas in the lounge of the Mason Pond Inn in Virginia. The rain nuzzles the windows and Manuel glances out, he seems bemused at the scenery of rain. This tawny inhabitant of the Arizona cactus country. His voice is faintly granular and soft as sand. Manuel was reared in the small town of Dinuba in California’s Central Valley. He is bold in his writing, shy in manner, a film aficionado. His body cuts a lean muscular form on the sofa. He wears dark jeans and a collared t-shirt. A chiseled jaw, thick raven black hair gelled into spikes, but his eyes are the thing. Large and tapering attractively at the corners, they lure with all the possibilities of the moment. One feels the charm in it.

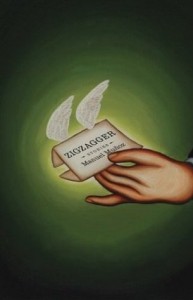

Munoz is the author of two short story collections: Zigzagger, published in 2003; and The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue in 2007, which was shortlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Prize. Munoz is a winner of the 2008 Whiting Writers Award, and a 2009 Pen/O. Henry prize. He is the recipient of fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts and National Endowment for the Arts. He lives in Tucson and teaches creative writing at the University of Arizona. His debut novel, What You See in the Dark, was released in 2011.

KI: What aspects of short story writing did you find helpful in novel writing, and what was foreign territory?

MM: What was foreign territory to me was scope. Really trying to get a handle on how plot had to drive the narrative. Sometimes you can get away with it in a short story, where you can make the most of the smallest moment, and that could be the center of an entire story. Whereas in the novel, I realized that my old tactics weren’t going to work. I really had to think out the plot. Chapter organization was where it helped me. I mean, it was a thread of narratives that involved, at one point, six characters. But as I read through three or four drafts— I did five in the end— by the time I got to the third draft is when I really had to start taking people out, or at least those whose points of view were peripheral. That helped a little bit: the compression that a short story forces you to have, I was trying to apply that to a chapter.

KI: So on the one hand, you can’t build around a single scene or a moment, but on the other there’s this problem where things get too big and you have to rein it in.

MM: Way too big. Even as late as the forth draft I had a chapter that was from the point of view of a police officer. This police officer goes to Teresa’s apartment and takes inventory of this place. But my agent asked me, “Is this the only reason that you have this guy’s point of view, because you have to get into that apartment?” And when the answer to that was, unfortunately, yes… that’s not enough, that’s not enough. And so I had to put it out.

MM: Way too big. Even as late as the forth draft I had a chapter that was from the point of view of a police officer. This police officer goes to Teresa’s apartment and takes inventory of this place. But my agent asked me, “Is this the only reason that you have this guy’s point of view, because you have to get into that apartment?” And when the answer to that was, unfortunately, yes… that’s not enough, that’s not enough. And so I had to put it out.

KI: I like the way you manipulate time. The plot shifts, turns back on itself, covers many years and circles around the murder. Talk about the considerations and decisions that go into structuring a novel. How did you decide to structure it this way?

MM: I’m glad you mentioned time, because time for me was the big discovery. I was very linear for a long time. But around draft three or four I realized that part of the problem was that I was leading up to a murder and I couldn’t decide on point of view. Should it be with Dan Watson or should it be with Teresa? And either way it’s just like, This isn’t working. And then a couple of things happened. I am a big fan of Joan Silber, I’ve said this many times. Grey Wolf has a great little series called, The Art of… And they have several of them. [Silber] has one called The Art of Time in Fiction. And of course I read through it. I was really afraid to say, Well, what if I don’t work in a linear way? And it opened up lots of possibilities. Now I know what I really get excited about in a particular chapter. Did everything in the novel have to lead to the murder? I realized, No, it doesn’t, other things can happen. I’m going to allow myself to do a lot more investigation of how a small town operates, which is really what the novel’s about.

KI: Sensuality is a major theme here. But there’s more going on than kissing and groping: there’s coming of age, there’s experience confronting inexperience, there’s learning, there’s shame. What interests you about sensuality and how do you approach it in writing?

KI: Sensuality is a major theme here. But there’s more going on than kissing and groping: there’s coming of age, there’s experience confronting inexperience, there’s learning, there’s shame. What interests you about sensuality and how do you approach it in writing?

MM: Oh man. That’s a great question. I mean, I tell my students that sex and desire in literature, when it’s done well, is most interesting to me when the psychology is allowed into the picture. That’s when it becomes really messy, exciting, frightening. All of those very intense emotions that have nothing to do with a physical reaction can come to the fore if you pay attention to interiority. It’s a chance to be very honest. Not about physical appearances and things, but more about having a character say, “Why have I allowed this? What am I getting into?” I love what that can bring. It is about shame. That just opens a door to a lot of very exciting things that can go on in the mind and the character. I’ve been joking many times, talking about the ending of this novel: I love that people sort of ignore the fact that it ends with a hand job!

KI: Candy’s giving a hand job while imagining the murder.

MM: Exactly. And people get so wrapped up in the fact that, Oh, this is how the murder has happened, and they ignore how it came to be on the page. I kind of love that.

KI: I want to talk about using song and cinema in the novel. I really like this moment where there’s a distinction between how Dan and Teresa play the guitar that is revealing of how each approaches the world, knows themselves. Talk about using song and music in a written story.

MM: Well that, to me, is harder than writing about sex. Because I’m not musical at all. Even just the— oh God, I’m setting up a horrible parallel here— the equipment… [laughs]. It makes me very nervous because I feel there has to be a sensuality behind the use of music. Because it’s someone’s outward expression, in that time, to reel somebody in. There’s a vulnerability to it.

KI: And film is a big part of the novel. Can you comment any more on that?

MM: Well, I’ve talked about Robert Altman a lot. I watched Nashua again on the big screen over the summer. And really, to me, it’s the very subtle gestures, things that maybe an average moviegoer wouldn’t notice. It’s camera movement. When a camera closes in on someone, I’m startled every time, it’s almost unnoticeable. And I’m sort of mimicking that, where I can start a paragraph with a very wide angle view of things, but then let the sentences narrow down so that we come down to the interiority of somebody who’s facing a problem. That’s one big one.

MM: Well, I’ve talked about Robert Altman a lot. I watched Nashua again on the big screen over the summer. And really, to me, it’s the very subtle gestures, things that maybe an average moviegoer wouldn’t notice. It’s camera movement. When a camera closes in on someone, I’m startled every time, it’s almost unnoticeable. And I’m sort of mimicking that, where I can start a paragraph with a very wide angle view of things, but then let the sentences narrow down so that we come down to the interiority of somebody who’s facing a problem. That’s one big one.

But a lot of it is just knowing that I can’t, as a writer, put in everything that films can. Film gives us color and light, sound, exact distance, and you can’t describe all those things, you have to choose what’s most important. Is it the color of the dress? If it’s the color of the dress then that’s what’s going to pop. All film has ever done is force me to pay attention.

KI: There’s a theme of knowing explored here. The characters imagine other characters, we see the disparity between the actual and perceived self. What is significant to you about this theme, is this something you grapple with in your own life?

MM: I mean that’s why, when people say it’s not a queer novel, I sort of feel it is in this respect. Because the act of coming out is: Here, here’s the whole real me. But what you battle against before that is the perception about you. And as a person who grew up in a small town, I knew what people thought of me. But it never got met with my ability to tell them my story. It can be very simple as, Yeah, I’m gay.

KI: But you want to tell them more than that?

MM: Absolutely. Because in their ability to tell a story about me, without knowing any kind of truth, they have the power to create false impressions about who I am. And that’s what fascinates me so much about how small towns operate. I’m pinning it specifically to the queer life. I mean, it applies to everybody. That’s why this novel didn’t have a gay character in it. Because the same problem is there. The universality of living in a place where people are making up stories about you can so dominate your life, even after you’re gone. Like poor Teresa, nobody let’s her go! Because nobody witnessed that murder, they’re going to start making up stories about it. That’s one way that I’ve really been almost obsessed with the question. How people tell each other particular truths.

KI: You use a lot of repetition of theme, of images, thoughts and phrases…

MM: There’s another thing I stole from movies. Hitchcock places such emphasis on making sure an audience sees an object or sees a moment, so that when that moment is refracted or reflected later on, we already know to have that image in mind. Like, in Psycho for example, the moment when the camera zooms in on the newspaper to tell us, Pay attention to the newspaper. So I took a lesson from that. I said, Well what can I do in fiction? So I thought really hard about what phrases I wanted to repeat. Because I thought that there was something coldly factual and unshakable about whatever it is that’s been repeated. You can’t get away from that fact. And that’s why I picked certain repetitions in particular.

KI: The way you structure this story, you weave the past into the present in a way that informs and expands themes, desires, attitudes, perspectives. And the past repeats itself, too, that’s another form of repetition. What role does the past play in the novel? How do you know which moments are significant?

MM: Again going back to Joan Silber’s The Art of Time in Fiction, the notion of backstory. It’s a classic problem. Both my undergraduates and my graduates will ask, “Well, how much do we put in?” And I think that had to do with who was going to get a past and who wasn’t. Arlene, for example, was the one who got that very long story about what happened to her brother. So that I could once again put her in a position of knowing what it’s like to be abandoned. But I also did it because I wanted to solve a technical problem. Because I kept asking myself, How would someone react to finding out their son has just murdered somebody and then taken off? Until I gave her a backstory, she was rendered a little flat to me. She was very flat in the drafts. When you see news reports about some horrible murder, in the back of your mind you might be wondering, How could that person have done that? In a way, it’s the wrong question. Because we want to look at the entirety of their life for the clues, and sometimes all that reveals is a pattern of behavior. For Arlene, she’s had men leaver her all her life. I mean this one happened to murder someone but it’s not anything that in some ways she’s not accustomed to. There’s a huge absence in her life, and now she has to deal with that absence, as opposed to dealing with the fact that she has a son that’s capable of this horrific moment. She has another way to think about what has happened rather than just the murder itself, and that’s why she needs backstory.

KI: Again, that informs, deepens the psychology of the moment.

MM: Yeah. And I didn’t think every character needed that. She became a more central figure than I anticipated. It turned out working very well, because her parallel in “Psycho” is the corpse. Mrs. Bates who’s kept in the cellar. It’s like, She has no story at all, keep her away. But, of course that woman had a story, it’s just the movie decided not to give it to us.

KI: Let’s talk about myth. Myth is given some import in the novel. In fable, in song, in the story itself dealing with the American dream, which is ultimately upended. What can myth do in a story?

MM: What fascinates me about it is that myth is an accepted story. As we go along, as a culture or a people or in this case a town, that story can get rewritten as people retell what they find central in a particular myth. I mean that’s the richness of having people be aware of how a story can get manipulated. That whole moment with Arlene and the storybook was for me to show that she had the intelligence to know that there might be a particular way to tell a story, because she had the clarity of mind to essentially think outside of the page. She has the power to imagine the whole tree when its picture is cut off halfway on the page. To imagine the whole cabin in the woods. And then to ask questions we should always be asking: “Well, who the hell built that cabin?” And she has that. Other people don’t. Like Candy the salesgirl certainly doesn’t. Or she does, but in a very self-serving way, it only answers one question: Who murdered that girl? That’s it. So that’s the big place in it. To know that there’s something communal about it, but that doesn’t necessarily make it democratic. Because we have to rely on people who are the more powerful storytellers to perpetuate a certain kind of myth. That’s why I like this whole myth, like you mention, of the American dream. We know that we all can’t have the picket fence and the little house and the two point five—you can’t. And yet, the engines that drive that vision of happiness are much more powerful than our doubts.

KI: Why did you choose to end the story as you did, with Candy imagining the murder?

MM: I tried to write the murder scene from Dan’s point of view. It was uncomfortable, it was ugly. But also, embedded in that choice was the motivation, which to me was not interesting. I still don’t care, really, why he did it. He did it. To me that’s what’s more important. And with Teresa I reached that whole problem where, if you take your character right up until the moment where he or she is meeting death, what do you do then? It can trigger this very high lyricism, as if death for any one of us is a beautiful moment, and it’s not. It’s not. So I kept running around thinking, How am I going to do this? This has to get told. And that’s when I decided, well, the technical problem is not a problem at all. Nobody witnessed this murder. And yet the whole town’s been fascinated by it. So what do you do when you run up into that truth? Someone’s going to recreate it in their head. And that’s when I said, That’s how to do it.

KI: This is a period piece, and it involves the Hitchcock film and Janet Leigh. Can you tell me more about researching 50’s Bakersfield, Hitchcock, Janet Leigh?

MM: There was some library work. I really targeted newspapers. To look for things that don’t even get mentioned in the book, but just to know. Like, How much does a car cost? What does an advertisement for a supermarket look like from back then? I just wanted to know. But I really went off on pictures. I think one of the reasons that I could describe that shoe store and the bowling alley is that those are all things that are in my town. And my town was stuck behind the times. The good thing about change not coming to small places like that is, places that were around in the 50’s, 60’s, 70’s are still there. It was only about six years ago that our town got a Starbucks. The first fast food restaurant that we got in our town, I was in high school, 1986.

KI: So some of the research is delving into your own memory?

MM: Yeah. Like to know what it’s like when you walk into the shoe store and hear the creak of the wood floor. It’s not polished concrete, it’s the wood floor, that’s slanted a little bit, and the simplicity patterns that nobody buys are way out in the back. I know how all that looks, and how it operates, because those places are still so present in all those towns, that you can just walk into them and feel like you’re transported back into another time. I mean, we had a place in my town, it was a gospel supply and typewriter store, that was the combined business. To me, that’s enough. It’s enough.

KI: Was it fun to get in Janet Leigh’s head?

MM: Oh yeah. Describe her clothes, the outfit she’s selected. It was easier than I thought because I felt an affinity for her as a fellow artist. There’s this doubt that fills you: How am I going to pull this off? And I was sort of taking her through the same steps. Maybe it wasn’t fair to think that she was an actress that doubted her abilities, but I wanted to make her like Arlene. Smarter than people give her credit for. And it’s a terrific performance. She did a phenomenal job with what I think is, on the page, a pretty crappy role. But she found the nuance within it, and that’s sort of the inspiration I get, that I can do the same in my own work. I don’t have to be loud and noisy with style.

KI: What writers should young writers be reading and why?

MM: It’s a hard question because I’m finding myself becoming a defender of the traditionalists. Like Alice Munro. The graduate students I have are very voracious readers, but they’re always looking for the new. And they’re at that stage where the traditional masters that people revere are there solely for the purpose of being knocked down. [Laughs]. I’m just hoping that somewhere along the line their minds open in a generous way. Actually I wouldn’t mind if they read a little more poetry. I wasn’t trained in poetry at all, but I read it to try to find something to wrap my head around in terms of sound or movement or pause.

KI: How much revision do you do? You say you did about five drafts?

MM: I did five drafts. And between the fourth and the fifth drafts I retyped the entire manuscript. So that I was reading every line to myself as I went through it, and basically asking myself, Is it doing more than just lazy exposition? And that’s a hard test. But it was a really good way to force myself to pay attention to detail. And that took me the entire summer. But it was really fun. It was the only time I had fun writing the book. First four drafts were awful, torture, I didn’t have fun writing. I have much more joy writing in short story.

KI: Really? Why do you think that is?

MM: Because I can see the end point. And I know what I’m trying to reach, and I can reach it quickly.

KI: And you couldn’t see the endpoint when you started this novel at all?

MM: [Shakes his head]. I had to finish a draft, then read through to see what I had, then reorganize. As I was telling you, I had to break my tendency to be linear. I had to break that. But I didn’t know until I got to the very end. And I had to say, okay, let’s start over. The first chapter of this book for the longest time was around chapter five, six. And it wasn’t written in that second person “You” at all. That came very late. But that was thinking and thinking and thinking… Why not just start off with the murder?

Manuel Munoz lives in Tucson and teaches creative writing at the University of Arizona. He is a winner of the 2008 Whiting Writers Award, and a 2009 Pen/O. Henry prize; his debut novel, What You See in the Dark, was released in 2011.

Ken Israel is the fiction editor at Phoebe.